Paxos

- Why is Paxos used in distributed systems?

- How does Paxos work?

- When does Paxos work? What are the limitations and practical issues of Paxos?

Why is Paxos used in distributed systems?

Paxos is a protocol for state machine replication in an asynchronous environment that admits crash failures.

A replicated state machine works by having multiple state machines, also called replicas, working in parallel, maintaining the same state. When the replicas receive requests from a client they update their state by executing the command in the request and reply to the client. This way, the state is automatically replicated by the replicas and in the event of a failure the state does not get lost, making the replicated state machine reliable.

It is easy for replicas to execute client commands in the same order and remain in sync if there is only one client or if multiple clients send their requests strictly sequentially as shown below:

In this example replicas receive requests from clients in the same order, execute the commands in the same order and respond to the clients, in effect staying in sync. For simplicity, it is assumed that a client can ignore duplicated responses.

But if multiple clients send requests to replicas in parallel, then different replicas might receive these requests in different orders and execute the commands in different orders, causing their local states to diverge from one another over time.

To prevent replicas from diverging in the presence of multiple clients sending requests in parallel, the order in which the client commands will be executed by replicas should be decided. We show this case below:

To decide the order in which the client commands will be executed the replicas can be thought of as having a sequence of slots that need to be filled with commands that make up the inputs to the state machine they maintain. In the example this sequence is shown as a table. Each slot is indexed by a slot number, starting from 1. Replicas receive requests from clients and assign them to specific slots, creating a sequence of commands. In the face of concurrently operating clients, different replicas may end up proposing different commands for the same slot. To avoid inconsistency, a consensus protocol chooses a single command from the proposals for every slot. In Paxos the subprotocol that implements consensus is called the multi-decree Synod protocol, or just Synod protocol for short. A replica awaits the decision before actually updating its sequence of commands in the table, executing the next command and computing a response to send back to the client that issued the request.

Essentially, the replicated state machine uses Paxos as an ordering entity which uses consensus to agree on which client command gets assigned to which slot. One has to make sure that the ordering entity itself is also reliable, that it can tolerate failures (at most f) just like the replicated state machine. To achieve reliability, Paxos is run by multiple specialized processes in a distributed fashion. This is not trivial because up to f processes running Paxos might fail at any time and, because there is no bound on timing for delivering and processing messages, it is impossible for other processes to know for certain that the process has failed.

How does Paxos work?

Paxos uses servers that have different roles in the execution of the protocol. The execution logic, and the insights behind the correctness of the protocol is covered here for each role.

How do Replicas work?

When a client κ wants to execute a command c=⟨κ,cid,op⟩, its stub routine broadcasts a ⟨request,c⟩ message to all replicas and waits for a ⟨response,cid,result⟩ message from one of the replicas.

The replicas can be thought of as having a sequence of slots. that need to be filled with commands that make up the inputs to the state machine. Each slot is indexed by a slot number. Replicas receive requests from clients and assign them to specific slots, creating a sequence of commands. A replica, on receipt of a ⟨request,c⟩ message, proposes command c for its lowest unused slot. We call the pair (s,c) a proposal for slot s.

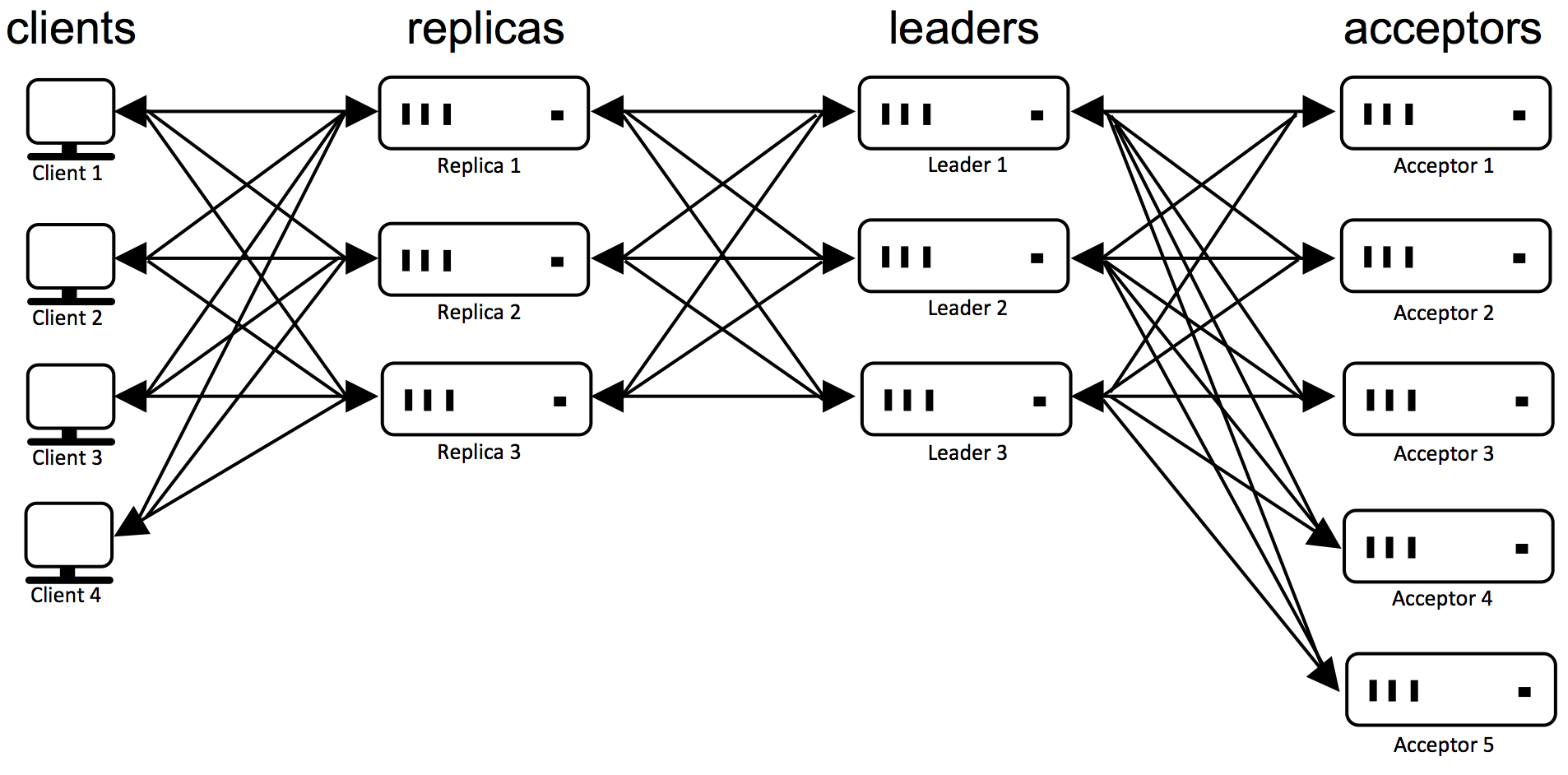

Replicas use the Synod protocol to choose a single command for each slot from the proposals they make. For each slot, a set of processes performs the Synod protocol to decide which command should be placed in that particular slot. A particular set of processes that are associated with a slot are commonly referred to as the configuration of that slot. The configuration of a slot contains the leader processes and acceptor processes, but not the replica processes. Leaders receive proposed commands from replicas and are responsible for choosing a single command for the slot. Thus, in order to tolerate f crash failures, Paxos needs at least f+1 leaders, always leaving at least 1 leader to order the commands proposed by replicas. A replica awaits the decision before actually updating its state and computing a response to send back to the client that issued the request.

Usually, the configuration for consecutive slots is the same. Sometimes, such as when a process in the configuration is suspected of having crashed, it is useful to be able to change the configuration. Paxos supports reconfiguration: a client can propose a special reconfiguration command, which is decided in a slot just like any other command. However, if s is the index of the slot in which a new configuration is decided, it does not take effect until slot s+𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆. This allows up to 𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆 slots to have proposals pending—the configuration of later slots may change. It is always possible to add new replicas—this does not require a reconfiguration of the leaders and acceptors.

Replica State

Each replica ρ maintains seven variables:

ρ.state, the replica’s copy of the application state, which we will treat as opaque. All replicas start with the same initial application state. ρ.slot_in, the index of the next slot in which the replica has not yet proposed any command. Initially 1. ρ.slot_out, the index of the next slot for which it needs to learn a decision before it can update its copy of the application state. Equivalent to the state’s version number (i.e., number of updates), and initially 1. ρ.requests, an initially empty set of requests that the replica has received and are not yet proposed or decided. ρ.proposals, an initially empty set of proposals that are currently outstanding. ρ.decisions, another set of proposals that are known to have been decided (also initially empty). ρ.leaders, the set of leaders in the current configuration. The leaders of the initial configuration are passed as an argument to the replica. Replica Invariants For correctness following invariants hold over the collected variables of replicas both before and after state transitions:

- R1: There are no two different commands decided for the same slot: ∀s,ρ1,ρ2,c1,c2:⟨s,c1⟩∈ρ1.decisions ∧ ⟨s,c2⟩∈ρ2.decisions⇒c1=c2

- R2: All commands up to slot_out are in the set of decisions: ∀ρ,s:1≤s<ρ.slot_out⇒∃c:⟨s,c⟩∈ρ.decisions

- R3: For all replicas ρ, ρ.state is the result of applying the commands ⟨s,cs⟩∈ρ.decisions to initial_state for all s up to slot_out, in order of slot number;

- R4: For each ρ, the variable ρ.slot_out cannot decrease over time.

- R5: A replica proposes commands only for slots it knows the configuration for: ∀ρ:ρ.slot_in<ρ.slot_out+𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆.

To understand the significance of such invariants, it is useful to consider what would happen if one of the invariants would not hold. If R1 would not hold, replicas could diverge, ending up in different states even if they have applied the same number of commands. Also, without R1, the same replica could decide multiple different commands for the same slot, because ρ1 and ρ2 could be the same process. Thus, the application state of that replica would be ambiguous.

Invariants R2-R4 ensure that, for each replica ρ, the sequence of the first ρ.slot_out commands is recorded and fixed. If any of these invariants were invalidated, a replica could change its history and end up with a different application state. The invariants do not imply that the slots have to be decided in order; they only imply that decided commands have to be applied to the application state in order and that there is no way to roll back.

Invariant R5 guarantees that replicas do not propose commands for slots that have an uncertain configuration. Because a configuration for slot s takes effect at slot s+𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆 and all decisions up to slot_out−1 are known, configurations up to slot ρ.slot_out+𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆−1 are known.

Replica Operational Description

Below you can find the pseudo-code for a Replica:

𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜 Replica(leaders,initial_state)

𝚟𝚊𝚛 state:=initial_state,slot_in:=1,slot_out:=1;

𝚟𝚊𝚛 requests:=∅,proposals:=∅,decisions:=∅;

𝚏𝚞𝚗𝚌𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 propose()

𝚠𝚑𝚒𝚕𝚎 slot_in<slot_out+𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆∧∃c:c∈requests 𝚍𝚘

𝚒𝚏 ∃op:⟨slot_in−𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆,⟨⋅,⋅,op⟩⟩∈decisions∧isreconfig(op) 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

leaders:=op.leaders;

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚒𝚏 ∄c′:⟨slot_in,c′⟩∈decisions 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

requests:=requests∖{c};

proposals:=proposals∪{⟨slot_in,c⟩};

∀λ∈leaders:send(λ,⟨propose,slot_in,c⟩);

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

slot_in:=slot_in+1;

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚠𝚑𝚒𝚕𝚎

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚏𝚞𝚗𝚌𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗

𝚏𝚞𝚗𝚌𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗 perform(⟨κ,cid,op⟩)

𝚒𝚏 (∃s:s<slot_out∧⟨s,⟨κ,cid,op⟩⟩∈decisions) ∨isreconfig(op) 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

slot_out:=slot_out+1;

𝚎𝚕𝚜𝚎

⟨next,result⟩:=op(state);

𝚊𝚝𝚘𝚖𝚒𝚌

state:=next; slot_out:=slot_out+1;

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚊𝚝𝚘𝚖𝚒𝚌

send(κ,⟨response,cid,result⟩);

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚏𝚞𝚗𝚌𝚝𝚒𝚘𝚗

𝚏𝚘𝚛 𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚛

𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑 receive()

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨request,c⟩:

requests:=requests∪{c};

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨decision,s,c⟩:

decisions:=decisions∪{⟨s,c⟩};

𝚠𝚑𝚒𝚕𝚎 ∃c′:⟨slot_out,c′⟩∈decisions 𝚍𝚘

𝚒𝚏 ∃c″:⟨slot_out,c″⟩∈proposals 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

proposals:=proposals∖{⟨slot_out,c″⟩};

𝚒𝚏 c″≠c′ 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

requests:=requests∪{c″};

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

perform(c′);

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚠𝚑𝚒𝚕𝚎

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑

propose();

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚏𝚘𝚛

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜

A replica runs in an infinite loop, receiving messages. Replicas receive two kinds of messages: requests and decisions. When it receives a request for command c from a client, the replica adds the request to set requests. Next, the replica invokes the function propose().

Function propose() tries to transfer requests from the set requests to proposals. It uses slot_in to look for unused slots within the window of slots with known configurations. For each such slot s, it first checks if the configuration for s is different from the prior slot by checking if the decision in slot s−𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆 is a reconfiguration command. If so, the function updates the set of leaders for slot s. Then the function removes a request r from requests and adds proposal (s,r) to the set proposals. Finally, it sends a ⟨propose,s,c⟩ message to all leaders in the configuration of slot s.

Decisions may arrive out-of-order and multiple times. For each decision message, the replica adds the decision to the set decisions. Then, in a loop, it considers which decisions are ready for execution before trying to receive more messages. If there is a decision c′ corresponding to the current slot_out, the replica first checks to see if it has proposed a command c″ for that slot. If so, the replica removes ⟨slot_out,c″⟩ from the set proposals. If c″≠c′, that is, the replica proposed a different command for that slot, the replica returns c″ to set requests so c″ is proposed again at a later time. Next, the replica invokes perform(c′).

The function perform() is invoked with the same sequence of commands at all replicas. First, it checks to see if it has already performed the command. Different replicas may end up proposing the same command for different slots, and thus the same command may be decided multiple times. The corresponding operation is evaluated only if the command is new and it is not a reconfiguration request. If so, perform() applies the requested operation to the application state. In either case, the function increments slot_out.

Maintenance of Replica Invariants

Note that decisions is ‘‘append-only’’ in that there is no code that removes entries from this set. Doing so makes it easier to formulate invariants and reason about the correctness of the code. We will discuss correctness-preserving ways of removing entries that are no longer useful in the context of optimizations later.

It is clear that the code enforces Invariant R4. The variables state and slot_out are updated atomically in order to ensure that Invariant R3 holds, although in practice it is not actually necessary to perform these updates atomically, as the intermediate state is not externally visible. Since slot_out is only advanced if the corresponding decision is in decisions, it is clear that Invariant R2 holds. A command is proposed for a slot only if that slot is within the current 𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆, and since replicas execute reconfiguration commands after a 𝚆𝙸𝙽𝙳𝙾𝚆 of operations it is ensured that Invariant R5 holds.

The real difficulty lies in enforcing Invariant R1. It requires that the set of replicas agree on the order of commands. For each slot, the Paxos protocol chooses a command from among a collection of commands proposed by clients. This is called consensus, and in Paxos the subprotocol that implements consensus is called the ‘‘multi-decree Synod’’ protocol, or just Synod protocol for short.

How do Acceptors work?

In the Synod protocol, there is an unbounded collection of ballots. Ballots are the key to liveness properties in Paxos. Each ballot has a unique leader. A leader can be working on arbitrarily many ballots, although it will be predominantly working on one at a time. A leader process has a unique identifier called the leader identifier. Each ballot has a unique identifier, called its ballot number. Ballot numbers are totally ordered, that is, for any two different ballot numbers, one is before or after the other. Do not confuse ballot numbers and slot numbers; they are orthogonal concepts. One ballot can be used to decide multiple slots, and one slot may be targeted by multiple ballots.

In this description, we will have ballot numbers be lexicographically ordered pairs of an integer and its leader identifier (consequently, leader identifiers need to be totally ordered as well). This way, given a ballot number, it is trivial to see who the leader of the ballot is. We will use one special ballot number ⊥ that is ordered before any normal ballot number, but does not correspond to any ballot.

During the Synod protocol leaders send messages to acceptors, so one can think of acceptors as servers, and leaders as their clients. Acceptors maintain the fault tolerant memory of Paxos, preventing conflicting decisions from being made. Acceptors use a voting protocol, allowing a unanimous majority of acceptors to decide without needing input from the remaining acceptors. Thus, in order to tolerate f crash failures, Paxos needs at least 2f+1 acceptors, always leaving at least f+1 acceptors to maintain the fault tolerant memory. Keep in mind that acceptors are not replicas of one another, because they get different sequences of input from leaders.

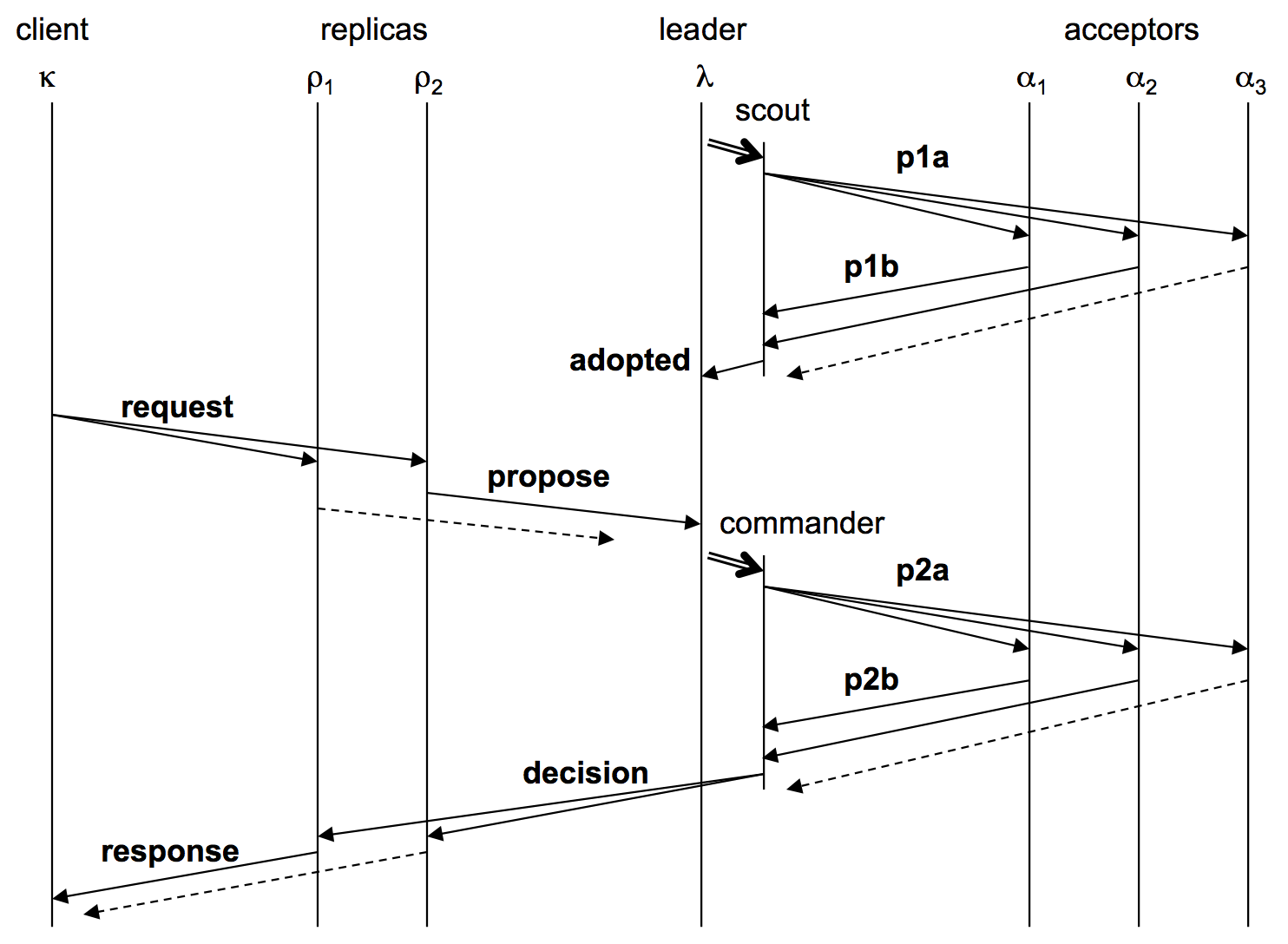

The figure below illustrates the communication patterns between the various types of processes in a setting where f=2.

Acceptor State

An acceptor is quite simple, as it is passive and only sends messages in response to requests. Its state consists of two variables. Let a pvalue be a triple consisting of a ballot number, a slot number, and a command. If α is the identifier of an acceptor, then the acceptor’s state is described by

- α.ballot_num: a ballot number, initially ⊥.

- α.accepted: a set of pvalues, initially empty.

Under the direction of messages sent by leaders, the state of an acceptor can change. Let p=⟨b,s,c⟩ be a pvalue consisting of a ballot number b, a slot number s, and a command c. When an acceptor α adds p to α.accepted, we say that α accepts p. An acceptor may accept the same pvalue multiple times. When α sets its ballot number to b for the first time, we say that α adopts b.

Acceptor Invariants

Knowing these invariants is an invaluable help to understanding the Synod protocol:

- A1: An acceptor can only adopt strictly increasing ballot numbers.

- A2: An acceptor α can only accept ⟨b,s,c⟩ if b=α.ballot_num;

- A3: Acceptor α cannot remove pvalues from α.accepted (we will modify this impractical restriction later).

- A4: Suppose α and α′ are acceptors, with ⟨b,s,c⟩∈α.accepted and ⟨b,s,c′⟩∈α′.accepted. Then c=c′. Informally, given a particular ballot number and slot number, there can be at most one proposed command under consideration by the set of acceptors.

- A5: Suppose that for each α among a majority of acceptors, ⟨b,s,c⟩∈α.accepted. If b′>b and ⟨b′,s,c′⟩∈α′.accepted, then c=c′.

It is important to realize that Invariant A5 works in two ways. In one way, if all acceptors in a majority have accepted a particular pvalue ⟨b,s,c⟩, then any pvalue for a later ballot will contain the same command c for slot s. In the other way, suppose some acceptor accepts ⟨b′,s,c′⟩. At a later time, if any majority of acceptors accepts pvalue ⟨b,s,c⟩ on an earlier ballot b<b′, then c=c′.

Acceptor Operational Description

Below you can find the pseudo-code for an Acceptor:

𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜 Acceptor()

𝚟𝚊𝚛 ballot_num:=⊥,accepted:=∅;

𝚏𝚘𝚛 𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚛

𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑 receive()

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨p1a,λ,b⟩:

𝚒𝚏 b>ballot_num 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

ballot_num:=b;

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

send(λ,⟨p1b,self(),ballot_num,accepted⟩);

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨p2a,λ,⟨b,s,c⟩⟩:

𝚒𝚏 b=ballot_num 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

accepted:=accepted∪{⟨b,s,c⟩};

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

send(λ,⟨p2b,self(),ballot_num⟩);

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚏𝚘𝚛

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜

The Acceptor runs in an infinite loop, receiving two kinds of request messages from leaders (note the use of pattern matching):

- ⟨p1a,λ,b⟩: Upon receiving a ‘‘phase 1a’’ request message from a leader with identifier λ, for a ballot number b, an acceptor makes the following transition. First, the acceptor adopts b if and only if it exceeds its current ballot number. Then it returns to λ a ‘‘phase 1b’’ response message containing its current ballot number and all pvalues accepted thus far by the acceptor.

- ⟨p2a,λ,⟨b,s,c⟩⟩: Upon receiving a ‘‘phase 2a’’ request message from leader λ with pvalue ⟨b,s,c⟩, an acceptor makes the following transition. If the current ballot number equals~b, then the acceptor accepts ⟨b,s,c⟩. The acceptor returns to λ a ‘‘phase 2b’’ response message containing its current ballot number.

Maintenance of Acceptor Invariants

The code enforces Invariants A1, A2, and A3. For checking the remaining two invariants, which involve multiple acceptors, we have to study what a leader does first, which is described in the following subsections.

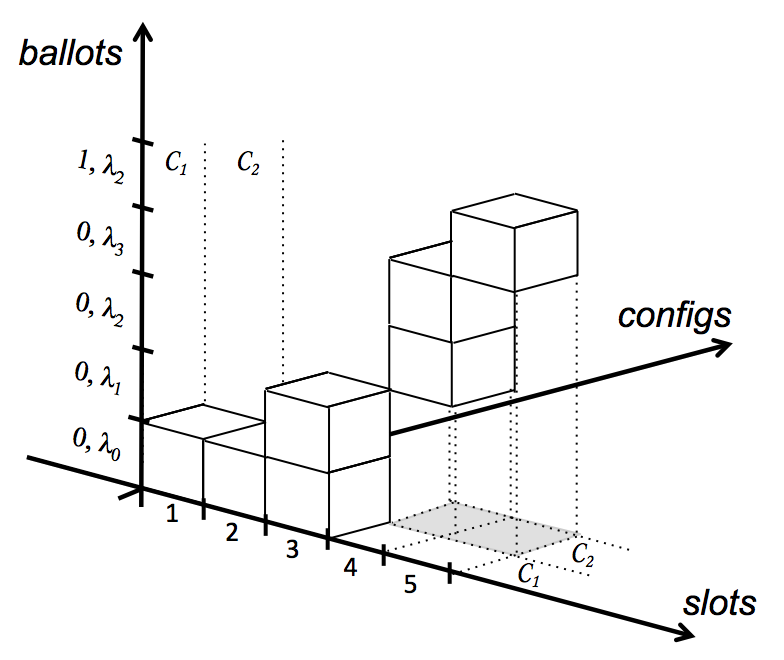

An instance of the Synod protocol uses a fixed configuration C consisting of at least f+1 leaders and 2f+1 acceptors. For simplicity, assume configurations have no processes in common. Instances follow each other, creating a reconfigurable protocol. The 3D graph below shows the relation between ballots, slots, and configurations. A leader can use a single ballot to decide multiple slots, as in the case for slots 1 and 2. Multiple leaders might use multiple ballots during a single slot, as shown in slot 3. A configuration can have multiple ballots and can span multiple slots, but each slot and each ballot has only one configuration associated with it.

In the Synod protocol slot numbers and ballot numbers are orthogonal concepts. One ballot can be used to decide on multiple slots, like in slot 1 and slot 2. A slot may be considered by multiple ballots, such as in slot 3. A configuration can span multiple ballots and multiple slots, but they each belong to a single configuration.

According to Invariant A4, there can be at most one proposed command per ballot number and slot number. The leader of a ballot is responsible for selecting a command for each slot, in such a way that selected commands cannot conflict with decisions on other ballots (Invariant A5).

How do Leaders work?

Leaders use Commander and Scout subprocesses to run the Synod protocol.

Leader Invariants

As we shall see, the following invariants hold in the Synod protocol:

- L1: For any ballot b and slot s, at most one command c is selected and at most one commander for ⟨b,s,c⟩ is spawned.

- L2: Suppose that for each αα among a majority of acceptors ⟨b,s,c⟩ ∈ α.accepted. If b′>b and a commander is spawned for ⟨b′,s,c′⟩, then c=c′.

Invariant L1 implies Invariant A4, because by L1 all acceptors that accept a pvalue for a particular ballot and slot number received the pvalue from the same commander. Similarly, Invariant L2 implies Invariant A5.

Commander

A leader may work on multiple slots at the same time. For each such slot, the leader selects a command and spawns a new process that we call a commander. While we present it as a separate process, the commander is really just a thread running within the leader. The commander runs what is known as phase 22 of the Synod protocol.

Below you can find the pseudo-code for a Commander:

𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜 Commander(λ,acceptors,replicas,⟨b,s,c⟩)

𝚟𝚊𝚛 waitfor:=acceptors;

∀α∈acceptors:send(α,⟨p2a,self(),⟨b,s,c⟩⟩);

𝚏𝚘𝚛 𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚛

𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑 receive()

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨p2b,α,b′⟩:

𝚒𝚏 b′=b 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

waitfor:=waitfor-{α};

𝚒𝚏 |waitfor|<|acceptors|/2 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

∀ρ∈replicas:

send(ρ,⟨decision,s,c⟩;

exit();

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚕𝚜𝚎

send(λ,⟨preempted,b′⟩);

exit();

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚏𝚘𝚛

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜

A commander sends a ⟨p2a,λ,⟨b,s,c⟩⟩ message to all acceptors, and waits for responses of the form ⟨p2b,α,b′⟩. In each such response b′≥b will hold. There are two cases:

-

If a commander receives ⟨p2b,α,b⟩from all acceptors in a majority of acceptors, then the commander learns that command cc has been chosen for slot s. In this case, the commander notifies all replicas and exits. To satisfy Invariant R1, we need to enforce that if a commander learns that cc is chosen for slot s, and another commander learns that c′ is chosen for the same slot s, then c=c′. This is a consequence of Invariant A5: if a majority of acceptors accept ⟨b,s,c⟩, then for any later ballot b′ and the same slot number s, acceptors can only accept ⟨b′,s,c⟩. Thus if the commander of ⟨b′,s,c′⟩ learns that c′ has been chosen for s, it is guaranteed that c=c′ and no inconsistency occurs, assuming—of course—that Invariant L2 holds.

-

If a commander receives ⟨p2b,α′,b′⟩from some acceptor α′, with b′≠b, then it learns that a ballot b′, which must be larger than b as guaranteed by acceptors, is active. This means that ballot bb may no longer be able to make progress, as there may no longer exist a majority of acceptors that can accept ⟨b,s,c⟩. In this case, the commander notifies its leader about the existence of b′, and exits.

Under the assumptions that at most a minority of acceptors can crash, that messages are delivered reliably, and that the commander does not crash, the commander will eventually do one or the other.

The leader must enforce Invariants L1 and L2. Because there is only one leader per ballot, Invariant L1 is trivial to enforce by the leader not spawning more than one commander per ballot number and slot number. To enforce Invariant L2, the leader runs what is often called phase 1 of the Synod protocol or a view change protocol for some ballot before spawning commanders for that ballot. The leader spawns a scout thread to run the view change protocol for some ballot bb. A leader starts at most one of these for any ballot bb, and only for its own ballots.

Scout

Below you can find the pseudo-code for a scout. The code is similar to that of a commander, except that it sends and receives phase 1 messages instead of phase 2 messages.

𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜 Scout(λ,acceptors,b)

𝚟𝚊𝚛 waitfor:=acceptors, pvalues:=∅;

∀α∈acceptors: send(α,⟨p1a,self(),b⟩);

𝚏𝚘𝚛 𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚛

𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑 receive()

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨p1b,α,b′,r⟩:

𝚒𝚏 b′=b 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

pvalues:=pvalues ∪ r;

waitfor:=waitfor-{α};

𝚒𝚏 |waitfor|<|acceptors|/2 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

send(λ,⟨adopted,b,pvalues⟩);

exit();

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚕𝚜𝚎

send(λ,⟨preempted,b′⟩);

exit();

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚏𝚘𝚛

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜

A scout completes successfully when it has collected ⟨p1b,α,b,rα⟩ messages from all acceptors in a majority, and returns a set of adopted messages to its leader λ. As we will see later, the leader uses the union of all pvalues accepted by this majority of acceptors, in order to enforce Invariant L2.

Leader State

Leader λ maintains three state variables:

- λ.ballot_num: a monotonically increasing ballot number, initially (0,λ).

- λ.active: a boolean flag, initially 𝚏𝚊𝚕𝚜𝚎false.

- λ.proposals: a map of slot numbers to proposed commands in the form of a set of ⟨slot number,command⟩ pairs, initially empty. At any time, there is at most one entry per slot number in the set.

Leader Operational Description

Below you can find the pseudo-code for a Leader:

𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜 Leader(acceptors,replicas)

𝚟𝚊𝚛 ballot_num=(0,self()),active=𝚏𝚊𝚕𝚜𝚎,proposals=∅;

spawn(Scout(self(),acceptors,ballot_num));

𝚏𝚘𝚛 𝚎𝚟𝚎𝚛

𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑 receive()

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨propose,s,c⟩:

𝚒𝚏 ∄c′:⟨s,c′⟩∈proposals 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

proposals:=proposals∪{⟨s,c⟩};

𝚒𝚏 active 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

spawn(Commander(self(),acceptors,replicas,⟨ballot_num,s,c⟩);

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜e

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨adopted, ballot_num, pvals⟩:

proposals:=proposals ⊲ pmax(pvals);

∀⟨s,c⟩∈proposals:

spawn(Commander(self(),acceptors,replicas,⟨ballot_num,s,c⟩);

active:=𝚝𝚛𝚞𝚎;

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎

𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎 ⟨preempted,⟨r′,λ′⟩⟩:

𝚒𝚏 (r′,λ′)>ballot_num 𝚝𝚑𝚎𝚗

active:=𝚏𝚊𝚕𝚜𝚎;

ballot_num:=(r′+1, self());

spawn(Scout(self(),acceptors,ballot_num));

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚒𝚏

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚌𝚊𝚜𝚎

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚜𝚠𝚒𝚝𝚌𝚑

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚏𝚘𝚛

𝚎𝚗𝚍 𝚙𝚛𝚘𝚌𝚎𝚜𝚜

The leader starts by spawning a scout for its initial ballot number, and then enters into a loop awaiting messages. There are three types of messages that cause transitions:

- ⟨propose,s,c⟩: A replica proposes command c for slot number s.

- ⟨adopted,ballot_num,pvals⟩: Sent by a scout, this message signifies that the current ballot number ballot_num has been adopted by a majority of acceptors. If an adopted message arrives for an old ballot number, it is ignored. The set pvals contains all pvalues accepted by these acceptors prior to ballot_num.

- ⟨preempted,⟨r′,λ′⟩⟩: Sent by either a scout or a commander, it means that some acceptor has adopted ⟨r′,λ′⟩. If ⟨r′,λ′⟩>ballot_num, it may no longer be possible to use ballot ballot_num to choose a command.

A leader goes between passive and active modes. When passive, the leader is waiting for an ⟨adopted,ballot_num,pvals⟩ message from the last scout that it spawned. When this message arrives, the leader becomes active and spawns commanders for each of the slots for which it has a proposed command, but must select commands that satisfy Invariant L2. We will now consider how the leader goes about this.

When active, the leader knows that a majority of acceptors, say A, have adopted ballot_num and thus no longer accept pvalues for ballot numbers less than ballot_num, because of Invariants A1 and A2. In addition, it has all pvalues accepted by the acceptors in A prior to ballot_num. The leader uses these pvalues to update its own proposals variable. There are two cases to consider:

- If, for some slot s, there is no pvalue in pvals, then, prior to ballot_num, it is not possible that any pvalue has been chosen or will be chosen for slot s. After all, suppose that some pvalue ⟨b,s,c⟩ were chosen, with b<ballot_num. This would require a majority of acceptors A′ to accept ⟨b,s,c⟩, but we have responses from a majority A that have adopted ballot_num and have not accepted, nor can accept, pvalues with a ballot number smaller than ballot_num, by Invariants A1 and A2. Because both A and A′ are majorities, A∩A′ is non-empty—some acceptor in the intersection must have violated Invariant A1, A2, or A3, which we assume cannot happen. Because no pvalue has been or will be chosen for slot s prior to ballot_num, the leader can propose any command for that slot without causing a conflict on an earlier ballot, thus enforcing Invariant L2.

- Otherwise, let ⟨b,s,c⟩ be the pvalue with the maximum ballot number for slot s. Because of Invariant A4, this pvalue is unique—there cannot be two different commands for the same ballot number and slot number. Also note that b<ballot_numb<ballot_num, because acceptors only report pvalues they accepted before adopting ballot_num. Like the leader of ballot_num, the leader of bb must have picked cc carefully to ensure that Invariant L2 holds, and thus if a pvalue is chosen before or at bb, the command it contains must be cc. Since all acceptors in A have adopted ballot_num, no pvalues between bb and ballot_num can be chosen, by Invariants A1 and A2. Thus, by using cc as a command, λ enforces Invariant L2.

This inductive argument is the crux for the correctness of the Synod protocol. It demonstrates that Invariant L2 holds, which in turn implies Invariant A5, which in turn implies Invariant R1 that ensures that all replicas apply the same operations in the same order.

Back to the code, after the leader receives ⟨adopted,ballot_num,pvals⟩, it determines for each slot the command corresponding to the maximum ballot number in pvals by invoking the function pmax. Formally, the function pmax(pvals) is defined as follows:

pmax(pvals)≡{⟨s,c⟩ | ∃b:⟨b,s,c⟩∈pvals ∧ ∀b′,c′:⟨b′,s,c′⟩∈pvals⇒b′≤b}

The update operator ⊲ applies to two sets of proposals. x⊲y returns the elements of y as well as the elements of x that are not in y. Formally:

x⊲y≡{⟨s,c⟩ | ⟨s,c⟩∈y ∨ (⟨s,c⟩∈x ∧∄c′:⟨s,c′⟩∈y)}Thus the line proposals:=proposals⊲pmax(pvals); updates the set of proposals, replacing for each slot number the command corresponding to the maximum pvalue in pvals, if any. Now the leader can start commanders for each slot while satisfying Invariant L2.

If a new proposal arrives while the leader is active, the leader checks to see if it already has a proposal for the same slot ((and has thus spawned a commander for that slot)) in its set proposals. If not, the new proposal will satisfy Invariant L2, and thus the leader adds the proposal to proposals and spawns a commander.

If either a scout or a commander detects that an acceptor has adopted a ballot number b, with b>ballot_num, then it sends the leader a 𝚙𝚛𝚎𝚎𝚖𝚙𝚝𝚎𝚍 message. The leader becomes passive and spawns a new scout with a ballot number that is higher than b.

Below is an example of a leader λ spawning a scout to become active, and a client κ sending a request to two replicas ρ1 and ρ2, which in turn send proposals to λ.

When does Paxos work? What about the impossibility of consensus result?

It would clearly be desirable that, if a client broadcasts a new command to all replicas, that it eventually receives at least one response. This is an example of a liveness property. It requires that if one or more commands have been proposed for a particular slot, that some command is eventually decided for that slot. Unfortunately, the Synod protocol as described does not guarantee this, even in the absence of any failure whatsoever. In fact, failures tend to be good for liveness. If all leaders but one fail, Paxos is guaranteed to terminate.

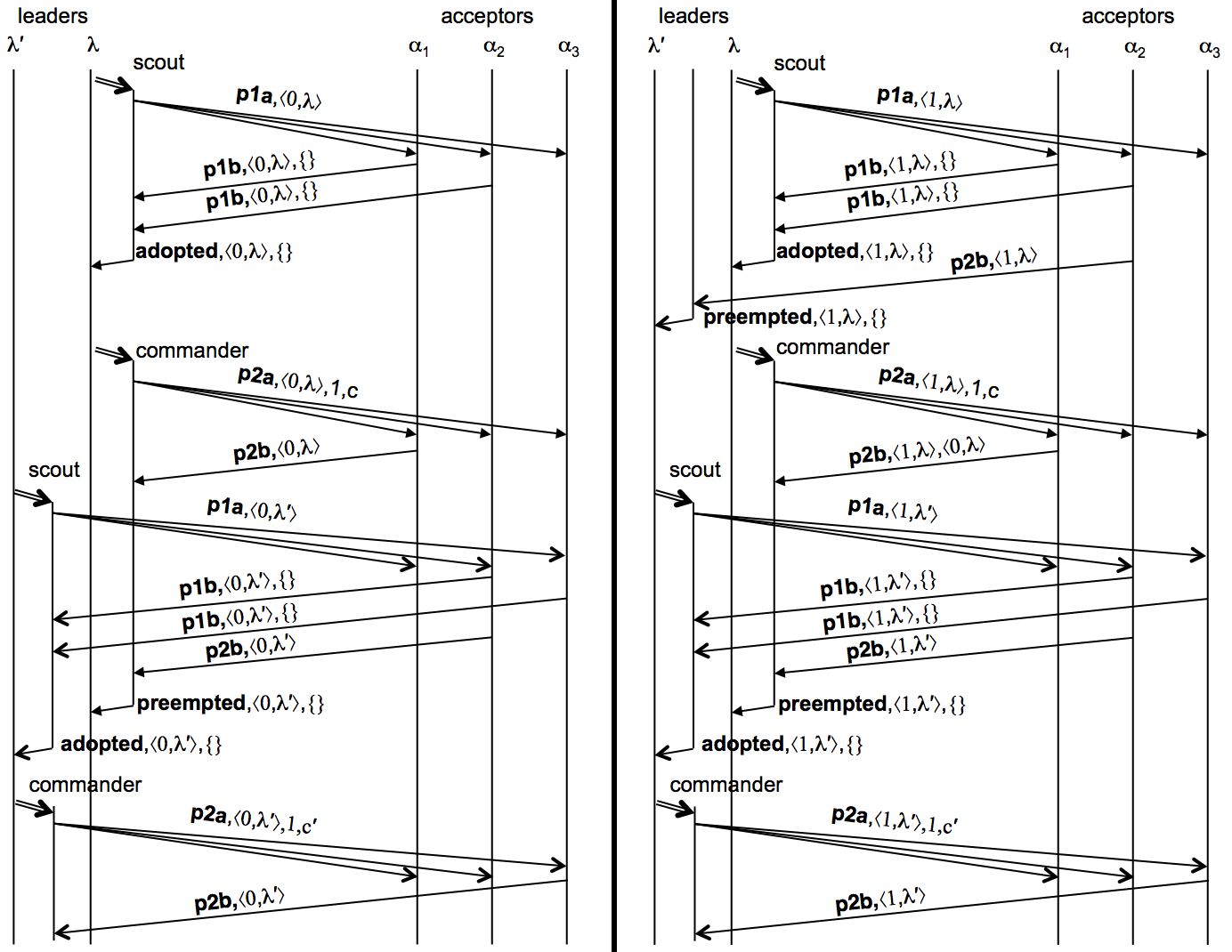

Consider the following scenario shown above, with two leaders with identifiers λ and λ′ such that λ<λ′. Both start at the same time, respectively proposing commands c and c′ for slot number 1. Suppose there are three acceptors, α1, α2, and α3. In ballot ⟨0,λ⟩, leader λ is successful in getting α1 and α2 to adopt the ballot, and α1 to accept pvalue ⟨⟨0,λ⟩,1,c⟩.

Now leader λ′ gets α2 and α3 to adopt ballot ⟨0,λ′⟩, which has a higher ballot number than ballot ⟨0,λ⟩ because λ<λ′. Note that neither α2 or α3 accepted any pvalues, so leader λ′ is free to select any proposal. Leader λ′ then gets α3 to accept ⟨⟨0,λ′⟩,1,c′⟩.

At this point, acceptors α2 and α3 are unable to accept ⟨⟨0,λ⟩,1,c⟩ and thus leader λ is unable to get a majority of acceptors to accept ⟨⟨0,λ⟩,1,c⟩. Trying again with a higher ballot, leader λ gets α1 and α2 to adopt ⟨1,λ⟩. The maximum pvalue accepted by α1 and α2 is ⟨⟨0,λ⟩,1,c⟩, and thus λ must propose c. Suppose λ gets α1 to accept ⟨⟨1,λ⟩,1,c⟩. Because acceptors α1 and α2 adopted ⟨1,λ⟩, they are unable to accept ⟨⟨0,λ′⟩,1,c′⟩. Trying to make progress, leader λ′ gets α2 and α3 to adopt ⟨1,λ′⟩, and gets α3 to accept ⟨⟨1,λ′⟩,1,c′⟩.

This ping-pong scenario can be continued indefinitely, with no ballot ever succeeding in choosing a pvalue. This is true even if c=c′, that is, the leaders propose the same command. The well-known ‘‘FLP impossibility result’’ demonstrates that in an asynchronous environment that admits crash failures, no consensus protocol can guarantee termination, and the Synod protocol is no exception. The argument does not apply directly if transitions have non-deterministic actions—for example changing state in a randomized manner. However, it can be demonstrated that such protocols cannot guarantee a decision either.

If we could somehow guarantee that some leader would be able to work long enough to get a majority of acceptors to adopt a high ballot and also accept a pvalue, then Paxos would be guaranteed to choose a proposed command. A possible approach could be as follows: when a leader λ discovers, through a 𝚙𝚛𝚎𝚎𝚖𝚙𝚝𝚎𝚍 message, that there is a higher ballot with leader λ′ active, rather than starting a new scout with an even higher ballot number, λ starts monitoring λ′ by pinging it on a regular basis. As long as λ′ responds timely to pings, λ waits patiently. Only if λ′ stops responding will λ select a higher ballot number and start a scout.

This concept is called failure detection, and theoreticians have been interested in the weakest properties failure detection should have in order to support a consensus algorithm that is guaranteed to terminate. In a purely asynchronous environment, it is impossible to determine through pinging or any other method whether a particular leader has crashed or is simply slow. However, under fairly weak assumptions about timing, we can design a version of Paxos that is guaranteed to choose a proposal. In particular, we will assume that both the following are bounded:

the clock drift of a process, that is, the rate of its clock is within some factor of the rate of real-time; the time between when a non-faulty process initiates sending a message, and the message having been received and handled by a non-faulty destination process. We do not need to assume that we know what those bounds are—only that such bounds exist. From a practical point of view, this seems entirely reasonable. Modern clocks progress certainly within a factor of 2 of real-time. A message between two non-faulty processes is likely delivered and processed within, say, a year. Even if the network was partitioned at the time the sender started sending the message, by the time a year has expired the message is highly likely to have been delivered and processed.

These assumptions can be exploited as follows: we use a scheme similar to the one described above, based on pinging and timeouts, but the value of the timeout interval depends on the ballot number: the higher the competing ballot number, the longer a leader waits before trying to preempt it with a higher ballot number. Eventually the timeout at each of the leaders becomes so high that some correct leader will always be able to get its proposals chosen.

For good performance, one would like the timeout period to be long enough so that a leader can be successful, but short enough so that the ballots of a faulty leader are preempted quickly. This can be achieved with a TCP-like AIMD (Additive Increase, Multiplicative Decrease) approach for choosing timeouts. The leader associates an initial timeout with each ballot. If a ballot gets preempted, the next ballot uses a timeout that is multiplied by some small factor larger than one. With each chosen proposal, this initial timeout is decreased linearly. Eventually the timeout will become too short, and the ballot will be replaced with another even if its leader is non-faulty.

Liveness can be further improved by keeping state on disk. The Paxos protocol can tolerate a minority of its acceptors failing, and all but one of its replicas and leaders failing. If more than that fail, consistency is still guaranteed, but liveness will be violated. A process that suffers from a power failure but can recover from disk is not theoretically considered crashed—it is simply slow for a while. Only a process that suffers a permanent disk failure would be considered crashed.

For completeness, we note that for liveness we also assumed reliable communication. This assumption can be weakened by using a fair links assumption: if a correct process repeatedly sends a message to another correct process, at least one copy is eventually delivered. Reliable transmission of a message can then be implemented by periodic retransmission until an ack is received. In order to prevent overload on the network, the time intervals between retransmissions can grow until the load imposed on the network is negligible. The fair links assumption can be weakened further, but such a discussion is outside the scope of this paper.

As an example of how liveness is achieved, a correct client retransmits its request to replicas until it has received a response. Because there are at least f+1 replicas, at least one of those replicas will not fail and will assign a slot to the request and send a proposal to the f+1 or more leaders. Thus at least one correct leader will try to get a command decided for that slot. Should a competing command get decided, the replica will reassign the request to a new slot and retry. While this may lead to starvation, in the absence of new requests, any outstanding request will eventually get decided in at least one slot.